동해-베링해 횡단구간 부유식물플랑크톤 기원의 유기분자생체지표 분포: PIP25 인덱스 사용 시 대양 환경 지시자로서의 적합성 검토

Copyright © 2017 The Geological Society of Korea

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

초록

본 연구에서는 서북극해 지역에서 과거 해빙 변화 복원에 사용되고 있는 프록시들 중 하나인 PIP25 인덱스에 대한 기초정보를 획득하기 위해 수층 입자 시료를 동해-베링해 횡단구간에서 2015년 7월 18일에서 28일 사이에 채취하였고, 북극 해빙 프록시 IP25 및 식물플랑크톤 기원의 유기분자생체지표인 삼중-불포화 highly branched isoprenoid (HBI triene)와 두 개의 sterol (brassicasterol 및 dinosterol)을 분석하였다. 또한 일반적으로 보고되고 있는 다른 sterol (cholesterol and 24-methylene-cholesterol)도 분석하였다. 샘플링 위치 및 계절의 특성과 일치하게 모든 분석시료에서 IP25은 검출되지 않았으나, HBI triene은 북서태평양과 베링해의 다섯 정점에서 검출되었다. 한편 sterol 화합물들은 모든 시료에서 검출되었다. 주목할 점은 brassicasterol 농도와 cholesterol 농도가 높은 양의 상관관계를 보이나, chlorophyll a와는 상관관계를 보이지 않는다는 점이다. 이러한 결과를 고려할 때, 본 연구 해역에서 brassicasterol은 식물플랑크톤 기원뿐만 아니라 동물 플랑크톤과 같은 다른 기원에 의한 영향을 받았을 것으로 보인다. 한편 dinosterol과 HBI triene 농도도 chl. a나 brassicasterol 농도와 상관관계를 보이지 않았으며, 이는 이들의 기원 또한 식물플랑크톤 이외의 다른, 다양한 기원의 영향을 받았을 수 있음을 지시한다. 결론적으로 본 연구 결과는 brassicasterol, dinosterol, 또는 HBI triene를 PIP25 인덱스에 식물플랑크톤 지시자로서 사용할 경우 서로 다른 경향성을 보일 수 있음을 시사하였다. 따라서 본 연구는 서북극해 지역에서의 PIP25 인덱스 사용과 관련해 이들 화합물의 해양 식물플랑크톤 지시자로서의 역할을 좀 더 명확하게 밝혀야 할 필요성을 보여 준다.

Abstract

In this study we collected suspended particulate matter (SPM) along a transect from the East Sea to the Bering Sea from 18 to 28 July in 2015. We then analyzed the samples for the Arctic sea ice proxy IP25 together with various phytoplankton-derived lipids including a tri-unsaturated highly branched isoprenoid (HBI triene) and two sterols (brassicasterol and dinosterol) to assess the suitability of these compounds for the so-called PIP25 index in the western Arctic region as a proxy for sea ice change in the past. The distributions of some other commonly reported sterols (cholesterol and 24-methylene-cholesterol) were also investigated. IP25 could not be detected in any of the samples analyzed, consistent with the nature of the sampling location and season, while the HBI triene was only detected at five sampling sites in the Northwest Pacific and the Bering Sea. In contrast, each of the sterols were detected at each sampling site. Interestingly, brassicasterol concentration showed a strong, positive relationship with cholesterol concentration, but no relationship with chlorophyll a, suggesting that the former might have been associated with not only marine phytoplankton but other sources in the study area, such as zooplankton. Dinosterol and HBI triene concentrations also showed no clear relationship with chl. a or brassicasterol concentrations, indicating likely different and diverse sources of these lipids in addition to marine phytoplankton. Our study suggests that the use of brassicasterol, dinosterol, or HBI triene, as strict phytoplankton markers for use with the PIP25 index, might result in misleading outcomes. Hence, it is clear that more work is needed to better constrain the use of these lipids as ice-free, open ocean biomarkers when using the PIP25 index in the western Arctic region.

Keywords:

ice proxy, biomarkers, highly branched isoprenoid, brassicasterol, dinosterol키워드:

해빙 프록시, 유기분자생체지표, highly branched isoprenoid, brassicasterol, dinosterol1. 서 론

기후 시스템에서 해빙은 태양 복사열 반사(알베도), 해양과 대기 사이의 열수지교환, 그리고 해양 순환 시스템에 영향을 미침으로써 전 지구적인 기후 변화를 제어하는 중요한 구성 요소이다(IPCC, 2013). 1978년부터 획득된 위성 수동 마이크로웨이브 자료에 따르면 북극 해빙의 범위는 전반적으로 감소 추세를 보이고 있다(e.g., Parkinson et al., 1999; Comiso et al., 2008). 하지만 이러한 해빙 변화의 관측 기록은 약 40년에 불과하여, 장기간 자연적 기후 변화에 따른 해빙 변화 복원은 불가능하다. 따라서 극지 해빙 변화의 패턴을 이해하고 해빙의 감소 원인을 규명을 위해서는 좀 더 긴 과거 해빙 복원 기록이 필요하다(e.g., de Vernal et al., 2013). 극지 해양에서 복원된 장기간의 해빙 기록들은 현재 진행되고 있는 기후 변화뿐만 아니라 미래의 기후 변화 예측에 사용되는 기후 모델들의 신뢰성을 높이기 위한 자료로 이용되기 때문에 매우 중요한 핵심 요소이다.

과거 해빙 변화를 복원하는 전형적인 방법들 중의 하나는 퇴적물 내에 존재하는 해빙 부착 미세조류의 화석을 현미경으로 관찰하여 종을 동정하는 방법이다(e.g., Gersonde and Zielinski, 2000). 해빙 조류는 빛이 투과되는 곳에서 서식하며 동물플랑크톤에 의해 섭식 되거나, 수층과 퇴적물에서의 분해 및 속성 과정을 통해 해저에 퇴적된다. 이러한 퇴적 과정에서 해빙 조류가 온전히 화석으로 보전되지 않을 경우 정확한 종 조성 파악이 힘들다.

과거 해빙 기록을 복원하는 또 다른 방법은 Belt et al. (2007)이 제안한 단일-불포화 화합물인 highly branched isoprenoid alkene (HBI)을 토대로 한 유기지화학적 방법이다. 단일-불포화 HBI는 북반구에서 봄철 동안 특정 해빙 규조류에 의해 생산되고, 해저로 운반, 퇴적되는 것으로 보고되었다(e.g., Brown et al., 2011). Belt 등(2007)은 이 단일-불포화 HBI를 다른 HBI들과 구별하기 위해 IP25 (Ice Proxy with 25 carbon atoms)라는 프록시로 명시하였다. 그 후, IP25는 해빙 규조류의 유기분자생체지표로서, 북극해역에서 과거 해빙 변화 복원을 위한 프록시로 널리 사용되고 있다(e.g., Massé et al., 2008; Belt et al., 2010, 2013; Fahl and Stein, 2012; Stein et al., 2012).

IP25의 생산은 주로 해빙의 가장자리에서 활발하며 영구해빙구역이나 해빙이 없는 대양에서는 생산이 아주 미미하거나 없는 것으로 알려져 있다(e.g., Müller et al., 2011). 따라서 IP25로는 이 두 지역을 구분하여 해빙 변화를 복원하기가 힘들다. 이러한 부분을 보완하기 위한 방법으로 해빙이 없는 대양에서 서식하는 부유성 식물플랑크톤의 유기분자생체지표와 IP25의 비, 즉 phytoplankton marker-IP25를 활용한 PIP25가 새로운 프록시로 Müller et al. (2011)에 의해 다음과 같이 제시되었다:

현재 PIP25 인덱스의 식물플랑크톤 유기분자생체지표 부분에는 brassicasterol (또는 epi-brassicasterol, e.g., Müller et al., 2011), dinosterol (e.g., Stoynova et al., 2013; Xing et al., 2014), 그리고 삼중 불포화 HBI triene (e.g., Belt et al., 2000, 2015; Massé et al., 2011)이 사용되고 있다. 하지만 PIP25 인덱스에 대양 식물플랑크톤의 지시자로서 이 세 유기분자생체지표 중 어떤 인자를 사용할 때 가장 정확하게 과거 해빙 변화를 복원 할 수 있는 지는 아직 명확하지 않다. 따라서 다양한 지역에서 이들 식물플랑크톤 유기분자생체지표의 분포도를 상호 비교하는 연구가 수행 될 필요가 있다.

본 연구에서는 동해-베링해 횡단구간에서 부유성 입자 물질을 채집하고 PIP25 인덱스 계산에 필요한 HBIs와 sterols을 분석하였다. 본 연구는 북서태평양 지역에서는 처음으로 PIP25 인덱스에 활용되고 있는 식물플랑크톤 유기분자생체지표들의 수층 분포도를 상호 비교하는데 목적이 있다. 결과적으로 베링해 및 서북극해에서 과거 해빙 복원의 한 방법으로써 PIP25 인덱스가 어떻게 활용 될 수 있는 지에 대한 좋은 기초 정보를 제시하고자 한다.

2. 시료 및 실험방법

2.1 부유성 입자 시료 채집

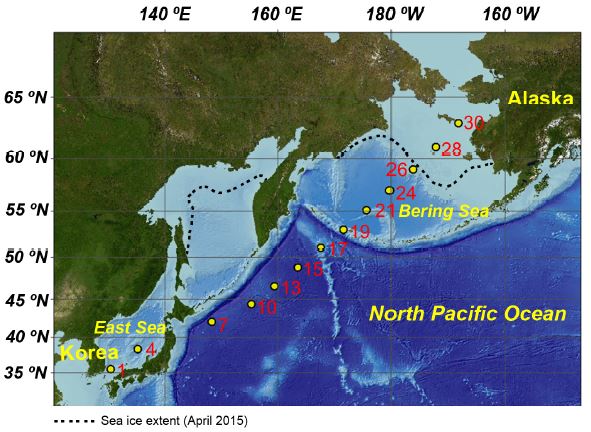

수층에서의 부유성 입자 시료 채집은 2015년 7월 18일부터 28일까지 극지연구소의 아라온호 이동 항해 구간(대한민국-알라스카) 중에 실시되었다(그림 1). 남서-북동 방향의 이동 항해 구간 동안 위도 약 2도 간격으로 시료를 채집하였으며, 수심 약 5 m 깊이에 장착된 채수 펌프를 통해 50-100 L의 해수를 폴리프로필렌 용기에 담은 후 GF/F (Whatman, 공극 0.7 μm, 직경 142 mm)를 이용하여 여과하였다. 여과된 시료는 알루미늄 호일에 싼 후 실험실로 운반되기 전까지 -80℃에 보관하였다.

2.2 지질 추출 및 분리

지질 추출 및 분리는 Belt et al. (2012)에 의해 발표된 방법을 따랐다. 동결 건조한 GF/F 시료에 정량 분석을 위한 내부표준물질(9-octylheptadec-8-ene: 9-OHD, 7-hexylnonadecane: 7-HND, 5-α-androstan-3β-ol) 100 ng을 주입하였다. 그 후 유기용매(dichloromethane (DCM):methanol (MeOH); 2:1, v:v)를 사용하여 15분 간 초음파 파쇄기로 지질을 추출하였고, 원심분리(2,500 rpm, 2 min)하여 상등액을 취하였다. 추출된 지질은 실리카 컬럼(63-200 µm)을 통해 점차적으로 극성이 강한 유기용매를 사용해 3개의 fraction으로 분리하였다. Fraction 1은 hexane으로 분리하였고, Fraction 2는 hexane:DCM (1:1, v:v), 그리고 Fraction 3은 DCM:MeOH (1:1, v:v)을 사용하여 분리하였다. Sterol 분석을 위해서는 Fraction 3에 100 μl N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) 주입한 후 70℃에서 1시간 동안 반응을 시키고, DCM을 이용하여 2 ml 유리 용기에 옮겨 담았다.

2.3 유기분자생체지표 분석

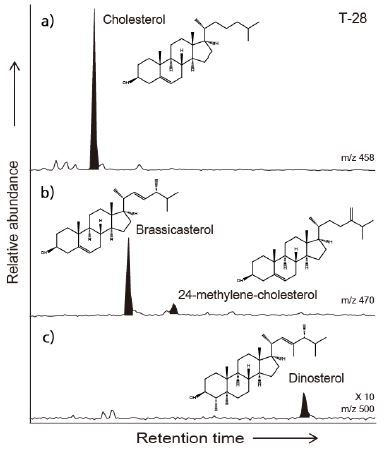

HBIs (Fraction 1) 및 sterols (Fraction 3) 분석은 영국 플리머스대학에서 Agilent 7890A gas chromatography (GC)와 연결된 5975C mass spectrometer (MS)를 사용하여 기존에 보고된 방식(e.g., Belt et al., 2012, 2013)에 따라 진행하였다. GC-MS 분석은 Agilent HP-5ms (30 m × 0.25 μm × 0.25 mm) 컬럼을 사용하여 진행하였다. GC 분석에 적용된 온도 조건은 40℃에서 300℃까지 분당 10℃의 비율로 온도를 증가시킨 후, 10분간 300℃에서 같은 온도를 유지하였다. 이동상 기체로 헬륨(1 ml/min)을 사용하였다. HBIs와 sterols 모두 total ion current (TIC) 방식과 selected ion monitoring (SIM) 방식으로 동시에 분석하였으며, 정성 분석은 TIC 결과를, 정량 분석은 SIM 결과를 사용하였다. IP25 그리고 HBI triene의 SIM 분석은 각각 m/z 350과 m/z 346을 사용하였고, cholesterol은 m/z 458, brassicasterol과 24-methylene-cholesterol은 m/z 470, 그리고 dinosterol은 m/z 500을 사용하였다(그림 2). HBIs는 Belt et al. (2012)의 방법에 따라 상대적인 반응계수(Relative Response Factor, RRF)를 고려하여 정량화하였다. Cholesterol, brassicasterol, 24-methylene-cholesterol은 Belt 등(2013)의 방법에 따라 각각의 단일표준물질과 내부표준물질(5α-androstan-3β-ol)의 RRF를 고려하여 정량화하였다. 반면 dinosterol 정량분석은 이 화합물의 단일표준물질이 없는 관계로, 한양대학교 표준퇴적물 시료에서 획득한 dinosterol의 single ion (m/z 500) 값과 total ion 값의 상대비, 즉 보정계수만 고려하여 반-정량적으로 수행하였다.

3. 결 과

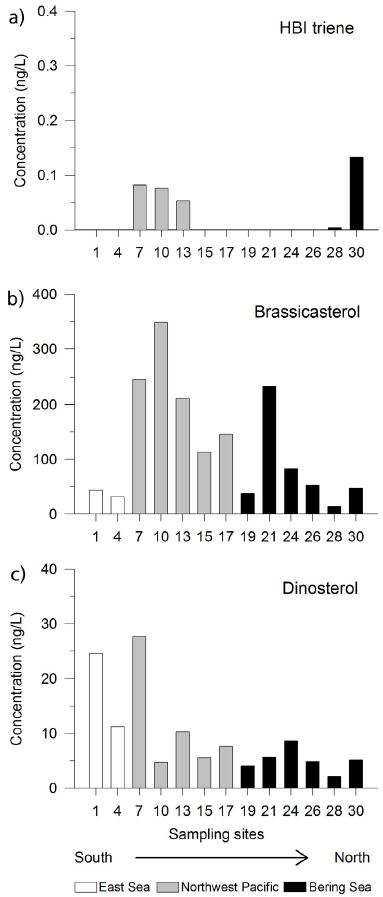

IP25는 동해-베링해 전 구간에서 검출되지 않았다(표 1). 하지만 HBI triene은 북서태평양 세 정점(T-7, T-10, T-13) 그리고 베링해 두 정점(T-28, T-30)에서 0.2 ng/L 이하의 낮은 농도로 검출 되었다(표 1; 그림 3). Sterol 중 본 연구에서 표적 화합물로 삼은 cholesterol, brassicasterol, 24-methylene-choles-terol, 그리고 dinosterol은 모든 분석 시료에서 검출 되었다(표 1). 이 중 brassicasterol (14-349 ng/L)이 sterol 화합물들 중에서 가장 높은 농도를 보였다(표 1; 그림 3). 한 편 cholesterol 농도(24-223 ng/L)는, brassicasterol 농도 보다는 낮으나 dinosterol (2-28 ng/L)과 24-methylene-cholesterol (3-25 ng/L) 농도 보다 높게 나타났다(표 1; 그림 3).

Information on the sampling sites and biomarker results obtained from this study. The chl. a data are obtained from the WOA01 (1 degree grid data, Conkright et al., 2002) for the summer months (July to September).

4. 토 의

해빙은 수층의 성층화, 영양염 및 빛 조절을 통해 극지 해역의 식물플랑크톤 생산력에 직접적으로 영향을 주는 주된 요인이다(e.g., Hill et al., 2005). 본 연구 지역 중 베링해 정점 T-28과 T-30은 겨울철 및 봄철에 해빙이 분포하는 해역에 위치한다(그림 1). 이 정점 주변의 표층 퇴적물에서 IP25의 검출이 확인된 바 있다(Stoynova et al., 2013). 일반적으로 해빙 용융이 일어나는 봄철에 해빙 밑바닥에서 해빙 부착 조류의 번식이 왕성하며 매우 응집된 구조를 형성한다(Syvertsen, 1991; Gradinger, 2009). 이때 IP25는 특정 해빙 부착 규조류에 의해 생성되며 해빙의 용융과 함께 해저에 퇴적된다(e.g., Brown et al., 2011). 하지만 본 연구에서는 베링해 정점을 포함한 모든 부유성 입자 시료에서 IP25가 검출 되지 않았다. 이러한 결과는 본 연구가 수행된 시기가 봄철 해빙 부착 규조류 생성이 활발한 시기로부터 3개월이 지난 후여서 IP25가 더 이상 수층에 존재 하지 않고 이미 해저로 침강 하였기 때문인 듯하다. 또한 IP25가 동해와 북서태평양에서도 검출되지 않은 것은 IP25가 해빙이 없는 대양 환경에서는 생산되지 않음을 시사한 기존의 다른 연구 결과들을 뒷받침한다(Belt et al., 2007; Brown et al., 2011; Belt and Müller, 2013). 하지만 IP25가 계절에 상관없이 해빙 분포에만 관계가 있는지, 즉 해빙의 분포해역에서 IP25가 봄철에만 생산되는지 혹은 봄철과 여름철에 모두 생산되는지를 명확히 밝히기 위해서는 서북극 해빙지역에서의 추가 연구가 필요하다.

한편 HBI triene은 IP25와는 달리 일부 북서태평양 정점과 베링해 정점에서 미량으로 검출되었다(그림 3a). HBI triene의 기원은 아직 명확하게 밝혀 지지 않은 상태이다(e.g., Belt et al., 2015). 지금까지 HBI triene은 Pleurosigma 속과 Rhizosoleia 속에 속하는 해양 규조류 종들에서만 검출 되었다(Belt et al., 2000; Rowland et al., 2001). 따라서 HBI triene은 후퇴하는 해빙 주변의 해양환경에서 규조류에 의해 생산될 것으로 추정된다(e.g., Collins et al., 2013). 이를 뒷받침하는 증거로는 수층 및 퇴적물에서 추출된 HBI triene의 탄소 안정동위원소 값이 -35 ~ -40 ‰로 IP25의 값(-14 ~ -23‰)에 비해 낮은 대양 식물플랑크톤 기원에 상응하는 값을 보인다는 점이다(Belt et al., 2008). 또한 본 연구에서 HBI triene이 해빙이 없는 시기에 북서태평양과 베링해 정점들에서 검출된 점은 HBI triene이 대양 식물플랑크톤에 의해 생산될 것이라는 기존의 주장과 일치하는 것이다. 하지만 100 L에 가까운 해수 여과량에도 검출된 HBI triene 농도가 전반적으로 낮았으며, 일부 정점에서만 검출되었다. 따라서 앞으로의 연구에서는 해수 여과량을 증가시킬 필요가 있으며, 서북극 해빙 지역을 포함 할 필요가 있다.

식물플랑크톤 기원의 유기분자생체지표로써 HBI triene뿐만 아니라 brassicasterol과 dinosterol도 함께 고려하였다. Brassicasterol은 규조류, 와편모조류 및 은편모조류 등 다수의 식물플랑크톤에서 검출 되며, 식물플랑크톤이 생산하는 sterol들 중에서도 높은 함량을 보인다(e.g., Volkman, 1986; Rampen et al., 2010). 한편 dinosterol은 와편모조류 기원의 지시자로 사용되고 있다(e.g., Volkman, 1986). 따라서 해양 퇴적물에서 관측되는 brassicasterol과 dinoster-ol은 해양에서 생산된 유기물, 즉 식물플랑크톤 기원의 지시자로 사용되고 있다(e.g., Xing et al., 2014; Dong et al., 2015; Hörner et al., 2016). 본 연구에서 brassicasterol의 농도(124±105 ng/L, n=13, 그림 3b)는 dinosterol (9±8 ng/L, n=13, 그림 3c)에 비해 10배 이상 높았다. 동해에서 brassicasterol (38±9 ng/L, n=2)은 북서태평양(213±92 ng/L, n=5)과 베링해(78±79 ng/L, n=6)에 비해 낮은 농도를 보인 반면, dinosterol의 농도는 동해(18±9 ng/L, n=2)에서 북서태평양(11±9 ng/L, n=2)과 베링해(5±2 ng/L, n=2)에 비해 높은 경향을 나타냈다(그림 3b, 3c). 이러한 결과는 시료 채집 기간(2015년 7월 18일 - 28일)인 여름철 동안에 동해가 다른 해역에 비해 와편모조류의 성장에 적합한 환경 이었음을 시사한다. 한편 본 연구의 brassicasterol과 dinosterol 결과는 베링해에서 규조류가 와편모조류 보다 우점종 임을 보여 준 기존의 연구 결과와 일치한다(Pleuthner et al., 2016). 본 연구에서 얻은 brassicasterol, cholesterol, 24-methylene-cholesterol 농도 값은 베링해에서 보고된 초여름 시기의 이들 농도 범위와 유사하다(Pleuthner et al., 2016). 그러나 본 연구 해역 중 dinosterol 농도가 가장 낮았던 베링해는 기존에 발표된 결과에 비해서는 높게 나타났다(Stoynova et al., 2013). 여기서 한가지 고려해야 할 점은, dinosterol 농도는 현재 다른 sterol과는 달리 단일표준물질이 없기 때문에 반-정량적으로 얻은 값이라는 것이다. 따라서 dinosterol과 다른 sterol들과의 정확한 농도 비교는 어렵다.

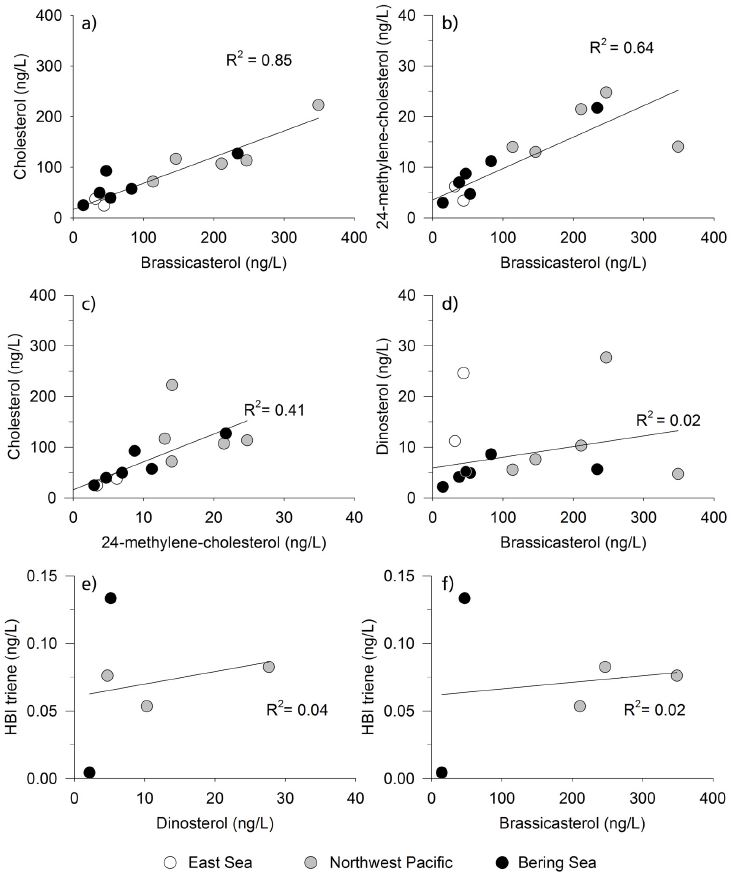

이 연구의 중요한 결과 중 하나는 brassicasterol이 cholesterol (그림 4a) 그리고 24-mehtylene-cholesterol(그림 4b)과 높은 양의 상관관계를 보인다는 점이다. 이로 인해 cholesterol과 24-methylene-cho-lesterol 또한 높은 양의 상관관계를 보인다(그림 4c). Cholesterol은 해양의 식물플랑크톤과 동물플랑크톤, 균류 등 다양한 생물에 의해 생성된다(e.g., Volkman, 1986). 또한 cholesterol은 육상으로부터 유기물 유입이 많은 해양환경에서도 널리 관측된다(e.g., Kim et al., 2016). 이러한 특성 때문에 cholesterol은 해양환경에서 특정 생물군에 대한 생체 지표로 사용되기 어렵다(e.g., Rampen et al., 2010). Brassicasterol 또한 해양 식물플랑크톤의 생산력 변화뿐만 아니라 해빙 및 육상 기원의 유입에 의해서도 영향을 받을 수 있다(Volkman, 1986; Fahl and Stein, 2012; Belt et al., 2013). 육상 기원의 유기물은 강을 통한 유입뿐만 아니라 대기중에서 바람에 의해 서도 유입될 수 있기 때문에(e.g., Huang et al., 2000) 동해-베링해 횡단구간에서 측정된 brassicasterol, 24-mehtylene-cholesterol 그리고 cholesterol은 해양 식물플랑크톤 생산력뿐만 아니라, 육상 기원의 유기물 유입에 의해서도 영향을 받을 수 있다. 한 예로 항공기를 이용하여 채집된 에어로졸 내의 유기 화합물의 분포를 살펴보면, 비록 채집된 시료의 계절적 차이가 있으나 중국 내륙에 비해 중국 동쪽 연안 지역에서 상대적으로 높은 sterol 농도를 보였다(Wang et al., 2007). 또한 봄철 황사의 유입 시기에 제주도 고산에서 관측된 에어로졸에서도 cholesterol 등이 검출되었다(Wang et al., 2009). 즉, 이러한 결과들은 육상 기원의 유기물이 하천을 통한 유입뿐만 아니라 대기를 통해서도 해양으로 유입이 가능하다는 것을 보여준다. 따라서 북서태평양지역의 정점들은 육지에서 멀리 떨어져 있지만 육상 기원 유기물의 유입 또한 고려 되어야 한다. 더욱이 연구 해역에서 brassicasterol, 24-methylene-cholesterol, 그리고 cholesterol이 chlorophyll a와 상관관계를 보이지 않는 점은 해양 식물플랑크톤뿐만 아니라 해양 동물플랑크톤 또는 육상 기원과 같은 다양한 기원의 영향을 받고 있음을 지시한다(그림 5b).

Scatter plots of phytoplankton-derived lipid biomarkers: (a) brassicasterol vs. cholesterol, (b) brassicasterol vs. 24-methylene-cholesterol, (c) 24-methylene-cholesterol vs. cholesterol, (d) brassicasterol vs. dinosterol, (e) dinosterol vs. HBI triene, and (f) brassicasterol vs. HBI triene.

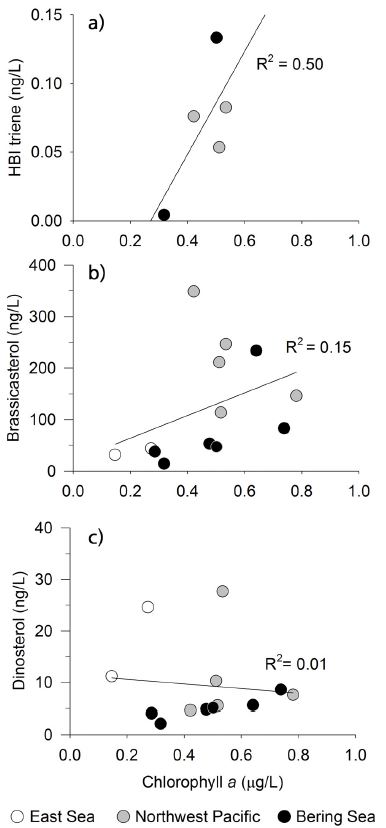

Scatter plots of phytoplankton-derived lipid biomarkers in comparison to chl. a: (a) chl. a vs. HBI triene, (b) chl. a vs. brassicasterol, and (c) chl. a vs. dinosterol.

Brassicasterol 처럼 dinosterol도 chl. a와 상관관계를 보이지 않았다(그림 5c). 그러나 HBI triene은 brassicasterol과 dinosterol에 비해서 chl. a와 높은 양의 상관관계를 보였다(그림 5a). 하지만 HBI triene은 다섯정점에서만 검출 되었고 그 농도 또한 매우 낮으므로 이러한 관계는 차 후 연구를 통해 검증되어야 할 것이다. 주목할 만한 점은 동해-베링해 횡단구간에서 brassicasterol과 dinosterol이 매우 낮은 상관관계를 보인다는 것이다(그림 4d). 또한 dinosterol과 HBI triene (그림 4e) 그리고 brassicasterol과 HBI triene (그림 4f)도 유사한 낮은 상관관계를 보였다. 이러한 결과들은 이들 화합물의 기원이 서로 다를 가능성을 시사한다. 이전 연구들에서 PIP25 인덱스에 dinosterol을 사용했을 때가 brassicasterol를 사용하였을 때 보다 해빙 조건을 더 잘 반영하는 것으로 보고된 바 있다(Stoynova et al., 2013; Polyak et al., 2016). 하지만 본 연구 결과는 brassicasterol, dinosterol, HBI triene을 PIP25 인덱스에 사용할 경우 해빙 조건과는 상관없이 서로 다른 경향성을 보일 수 있음을 시사한다. 하지만 본 연구에서 IP25가 검출되지 않았기 때문에 어떠한 생체 지표가 연구지역에서 PIP25 인덱스 사용에 좀 더 적합한 지는 판단할 수 없다. 따라서 서북극해 지역에서 PIP25 인덱스를 통해 과거 해빙 복원을 하기 위해서는 brassicasterol, dinosterol, 그리고 HBI triene의 해양 식물플랑크톤의 지시자로서 역할 및 그들의 해빙 분포와의 관계를 좀 더 명확하게 규명하는 연구가 수행되어야 할 것이다.

5. 결 론

본 연구에서는 동해-베링해 횡단구간에서 채집한 수층 입자 시료를 사용하여 과거 해빙 분포 복원에 사용되고 있는 PIP25 인덱스에 필요한 HBIs와 sterols을 분석하였다. 본 연구에서 표적으로 선택한 유기분자생체지표 중 IP25는 동해-베링해 전 구간에서 검출되지 않았지만, HBI triene은 일부 북서태평양과 베링해 정점에서 검출되었다. 반면 brassicasterol과 dinosterol은 모든 구간에서 검출되었다. 본 연구 결과는 brassicasterol이 cholesterol과는 강한 양의 상관관계를 보이나, dinosterol 및 HBI triene과는 상관관계가 거의 없음을 나타냈다. Dinosterol과 HBI triene의 상관관계도 보이지 않았다. 또한 이들 sterol들은 chl. a와도 뚜렷한 상관관계를 보이지 않았다. 이러한 결과들은 brassicasterol, dinosterol 그리고 HBI triene의 기원이 서로 다름을 시사하며, 이들의 분포가 해빙 분포보다 식물플랑크톤 조성 변화 등에 의해 더 많은 영향을 받은 것으로 사료된다. 주목할 점은 brassicasterol, dinosterol, HBI triene을 PIP25 인덱스에 사용할 경우 같은 해빙 조건 하에서 서로 다른 경향성을 보일 수 있다는 것이다. 따라서 서북극해 지역에서의 PIP25 인덱스 사용과 관련해 brassicasterol, dinosterol, 그리고 HBI triene의 식물플랑크톤 지시자로서의 역할에 관한 좀 더 많은 연구의 수행이 필요하다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 2017년 극지연구소에서 수행하는 연구정책‧지원과제 '척치해 및 로스해에서 활용 가능한 고해빙 프록시 개발 및 검증(PE16490)', 2016년 미래창조과학부의 재원으로 수행되는 한국연구재단 해양극지기초원천기술사업과제(2015M1A5A1037243), 그리고 2016년 해양수산부 재원으로 해양수산과학기술진흥원(동해 심층해수 및 물질 순환 기작 규명, 20160400)의 연구비로 수행하였다.

References

-

Belt, S.T., Allard, W.G., Massé, G., Robert, J.M., and Rowland, S.J., (2000), Highly branched isoprenoids (HBIs): Identification of the most common and abundant sedimentary isomers, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 64, p3839-3851.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-7037(00)00464-6]

-

Belt, S.T., Brown, T.A., Ringrose, A.E., Cabedo-Sanz, P., Mundy, C.J., Gosselin, M., and Poulin, M., (2013), Quantitative measurement of the sea ice diatom biomarker IP25 and sterols in Arctic sea ice and underlying sediments: Further considerations for palaeo sea ice reconstruction, Organic Geochemistry, 62, p33-45.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2013.07.002]

-

Belt, S.T., Brown, T.A., Rodriguez, A.N., Sanz, P.C., Tonkin, A., and Ingle, R., (2012), A reproducible method for the extraction, identification and quantification of the Arctic sea ice proxy IP25 from marine sediments, Analytical Methods, 4, p705.

[https://doi.org/10.1039/c2ay05728j]

-

Belt, S.T., Cabedo-Sanz, P., Smik, L., Navarro-Rodriguez, A., Berben, S.M.P., Knies, J., and Husum, K., (2015), Identification of paleo Arctic winter sea ice limits and the marginal ice zone: Optimised biomarker-based reconstructions of late Quaternary Arctic sea ice, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 431, p127-139.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2015.09.020]

-

Belt, S.T., Massé, G., Rowland, S.J., Poulin, M., Michel, C., and LeBlanc, B., (2007), A novel chemical fossil of palaeo sea ice: IP25, Organic Geochemistry, 38, p16-27.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2006.09.013]

-

Belt, S.T., Massé, G., Vare, L.L., Rowland, S.J., Poulin, M., Sicre, M.A., Sampei, M., and Fortier, L., (2008), Distinctive 13C isotopic signature distinguishes a novel sea ice biomarker in Arctic sediments and sediment traps, Marine Chemistry, 112, p158-167.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2008.09.002]

-

Belt, S.T., and Müller, J., (2013), The Arctic sea ice biomarker IP25: A review of current understanding, recommendations for future research and applications in palaeo sea ice reconstructions, Quaternary Science Reviews, 79, p9-25.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.12.001]

-

Belt, S.T., Vare, L.L., Massé, G., Manners, H.R., Price, J.C., MacLachlan, S.E., Andrews, J.T., and Schmidt, S., (2010), Striking similarities in temporal changes to spring sea ice occurrence across the central Canadian Arctic Archipelago over the last 7000 years, Quaternary Science Reviews, 29, p3489-3504.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.06.041]

-

Brown, T.A., Belt, S.T., Philippe, B., Mundy, C.J., Massé, G., Poulin, M., and Gosselin, M., (2011), Temporal and vertical variations of lipid biomarkers during a bottom ice diatom bloom in the Canadian Beaufort Sea: Further evidence for the use of the IP25 biomarker as a proxy for spring Arctic sea ice, Polar Biology, 34, p1857-1868.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-010-0942-5]

- Conkright, M.E., Locarnini, R.a., Garcia, H.E., O’Brien, T.D., Boyer, T.P., Stepens, C., and Antonov, J.I., (2002), World Ocean Atlas 2001: Objective analyses, data statistics, and figures CD-ROM documentation, National Oceanographic Data Center Internal Report (NOAA Atlas NESDIS), 17, p17.

-

Collins, L.G., Allen, C.S., Pike, J., Hodgson, D.A., Weckström, K., and Massé, G., (2013), Evaluating highly branched isoprenoid (HBI) biomarkers as a novel Antarctic sea-ice proxy in deep ocean glacial age sediments, Quaternary Science Reviews, 79, p87-98.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.02.004]

-

Comiso, J.C., Parkinson, C.L., Gersten, R., and Stock, L., (2008), Accelerated decline in the Arctic sea ice cover, Geophysical Research Letters, 35, p1-6.

[https://doi.org/10.1029/2007gl031972]

-

de Vernal, A., Gersonde, R., Goosse, H., Seidenkrantz, M., and Wolff, E.W., (2013), Sea ice in the paleoclimate system : the challenge of reconstructing sea ice from proxies e an introduction, Quaternary Science Reviews, 79, p1-8.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.08.009]

-

Dong, L., Li, L., Li, Q., Liu, J., Chen, Y., He, J., and Wang, H., (2015), Basin-wide distribution of phytoplankton lipids in the South China Sea during intermonsoon seasons: Influence by nutrient and physical dynamics, Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 122, p52-63.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2015.07.005]

-

Fahl, K., and Stein, R., (2012), Modern seasonal variability and deglacial/Holocene change of central Arctic Ocean sea-ice cover: New insights from biomarker proxy records, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, p351-352, p123-133.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2012.07.009]

-

Gersonde, R., and Zielinski, U., (2000), The reconstruction of late Quaternary Antarctic sea-ice distribution - the use of diatoms as a proxy for sea-ice, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 162, p263-286.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-0182(00)00131-0]

-

Gradinger, R., (2009), Sea-ice algae: Major contributors to primary production and algal biomass in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas during May/June 2002, Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 56, p1201-1212.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.10.016]

-

Hill, V., Cota, G., and Stockwell, D., (2005), Spring and summer phytoplankton communities in the Chukchi and Eastern Beaufort Seas, Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 52, p3369-3385.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2005.10.010]

- Hörner, T., Stein, R., Fahl, K., and Birgel, D., (2016), Postglacial variability of sea ice cover, river run-off and biological production in the western Laptev Sea (Arctic Ocean) - A high-resolution biomarker study, Quaternary Science Reviews, 143, p133-149.

-

Huang, Y., Dupont, L., Sarnthein, M., Hayes, J.M., and Eglinton, G., (2000), Mapping of C4 plant input from North West Africa into North East Atlantic sediments, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 64, p3505-3513.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-7037(00)00445-2]

- IPCC in Climate Change, (2013), The Physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate changes (eds. Stocker, T.F. et al.), Cambridge Univ. Press, p1535.

-

Kim, M., Jung, J., Jin, Y., Y, Han, G.M., Lee, T., Hong, S.H., Yim, U.H., Shim, W.J., Choi, D., and Kannan, N., (2016), Origins of suspended particulate matter based on sterol distribution in low salinity water mass observed in the offshore East China Sea, Marine Pollution Bulletin, 108, p281-288.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.04.049]

- Massé, G., Belt, S.T., Crosta, X., Schmidt, S., Snape, I., Thomas, D.N., and Rowland, S.J., (2011), Highly branched isoprenoids as proxies for variable sea ice conditions in the Southern Ocean, Antarctic Science, 23, p487-498.

- Massé, G., Rowland, S.J., Sicre, M.-A., Jacob, J., Jansen, E., and Belt, S.T., (2008), Abrupt climate changes for Iceland during the last millennium: Evidence from high resolution sea ice reconstructions, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 269, p565-569.

- Müller, J., Wagner, A., Fahl, K., Stein, R., Prange, M., and Lohmann, G., (2011), Towards quantitative sea ice reconstructions in the northern North Atlantic: A combined biomarker and numerical modelling approach, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 306, p137-148.

-

Parkinson, C.L., Cavalieri, D.J., Gloersen, P., Zwally, H.J., and Comiso, J.C., (1999), Arctic sea ice extents, areas, and trends, 1978-1996, Journal of Geophysical Research, 104, p20837-20856.

[https://doi.org/10.1029/1999jc900082]

-

Polyak, L., Belt, S.T., Cabedo-Sanz, P., Yamamoto, M., and Park, Y.-H., (2016), Holocene sea-ice conditions and circulation at the Chukchi-Alaskan margin, Arctic Ocean, inferred from biomarker proxies, The Holocene, 26, p1810-1821.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683616645939]

-

Pleuthner, R.L., Shaw, C.T., Schatz, M.J., Lessard, E.J., and Harvey, H.R., (2016), Lipid markers of diet history and their retention during experimental starvation in the Bering Sea euphausiid Thysanoessa raschii, Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 134, p190-203.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2015.08.003]

-

Rampen, S.W., Abbas, B.a., Schouten, S., and Damsté, J.S.S., (2010), A comprehensive study of sterols in marine diatoms (Bacillariophyta): Implications for their use as tracers for diatom productivity, Limnology and Oceanography, 55, p91-105.

[https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2010.55.1.0091]

-

Rowland, S.J., Belt, S.T., Wraige, E.J., Roussakis, C., Robert, J., and Masse, G., (2001), Effects of temperature on polyunsaturation in cytostatic lipids of Haslea ostrearia, Phytochemistry, 56, p597-602.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00434-9]

- Stein, R., Fahl, K., and Müller, J., (2012), Proxy reconstruction of Cenozoic Arctic Ocean sea-ice history - From IRD to IP25-, Polarforschung, 82, p37-71.

-

Stoynova, V., Shanahan, T.M., Hughen, K.A., and de Vernal, A., (2013), Insights into Circum-Arctic sea ice variability from molecular geochemistry, Quaternary Science Reviews, 79, p63-73.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.10.006]

-

Syvertsen, E.E., (1991), Ice algae in the Barents Sea: types of assemblages, origin, fate and role in the ice‐edge phytoplankton bloom, Polar Research, 10, p277-288.

[https://doi.org/10.3402/polar.v10i1.6746]

-

Volkman, J.K., (1986), A review of sterol markers for marine and terrigenous organic matter, Organic Geochemistry, 9, p83-99.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6380(86)90089-6]

-

Wang, G., Kawamura, K., Hatakeyama, S., Takami, A., Li, H., and Wang, W., (2007), Aircraft measurement of organic aerosols over China, Environmental Science and Technology, 41, p3115-3120.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/es062601h]

-

Wang, G., Kawamura, K., and Lee, M., (2009), Comparison of organic compositions in dust storm and normal aerosol samples collected at Gosan, Jeju Island, during spring 2005, Atmospheric Environment, 43, p219-227.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.09.046]

-

Xing, L., Zhao, M., Gao, W., Wang, F., Zhang, H., Li, L., Liu, J., and Liu, Y., (2014), Multiple proxy estimates of source and spatial variation in organic matter in surface sediments from the southern Yellow Sea, Organic Geochemistry, 76, p72-81.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2014.07.005]